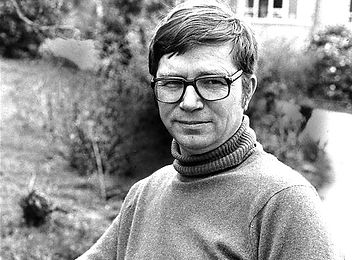

An appreciation of the author Colin Wilson (1931-2013) - philosopher, critic, novelist

Eagles & Earwigs: Essays on Books and Writers

Colin Wilson

Eyewear Publishing (UK £15.99, October 2018)

Existential criticism, formulated by Colin Wilson 60 years ago, remains valid today despite having been overlooked in the literary world. His radical theory (as essentially a mimetic, as opposed to a semiotic, one) could have changed the way we think about literature – and it still ought.

This is brought home forcefully by the new edition of Wilson’s key 1965 volume of literary criticism which, even after more than half a century, remains important for the way Wilson deals boldly with the question literary academics and critics shy away from: the purpose and value of literature.

The new 400-page edition – under Wilson’s preferred title as the original publisher, to Wilson’s irritation, changed the title to Eagle & Earwig – comes with invaluable editorial notes by Wilson’s bibliographer Colin Stanley and an introduction by the writer and Wilson scholar Gary Lachman.

The Eagles & Earwigs essays – some dating from 1957 – are grouped in three sections: the first dealing with the role of literature, at a time when ‘a crisis has been reached in the history of human development’, the second with visionary writers whose work had engaged Wilson, and the third with ‘the problem of being a writer in the 20th century’.

Works of literature, Wilson maintained, had to be judged by standards of meaning, as well as by the impact on the sensibilities; in other words, not just by aesthetics, or artist sufficiency, alone (the usual critical position). Crucially: ‘No writer is justified in declaring that human existence is meaningless.’

This was why, for a famous example, Wilson had no patience with Samuel Beckett’s defeatism: ‘And such was the confusion and irrationality that prevailed in his time, and to a large extent still prevails, that he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his efforts to discourage us all.’ Wilson wrote that in a book published only 20 years ago (The Books in my Life, 1998) and that confusion and irrationality remains, perhaps to a larger extent today.

Artistic development

As Gary Lachman, referring to Wilson’s view that one can be a bad novelist but still a writer of genius, says in his preface: ‘All the technique in the world cannot make up for having nothing to say’ – or having nothing meaningful to say. How true that is!

Long-term artistic development and a negative philosophy, as expressed by so many writers in the 20th century, are incompatible, Wilson stated. His statement continues to ring true. He saw that pessimism, which still pervades much ‘serious’ literature and impresses Sunday supplement reviewers and awards panels today, is ‘an outcome of the combination of laziness and forgetfulness ... It has no objective justification.’

Re-reading Eagles & Earwigs – indeed, an incisive work of existential criticism – three things strike one immediately. The first is how valuable existential criticism would still be if applied today, directed primarily, as it would be, at ‘serious’ or ‘literary’ fiction and poetry. See my review of Colin Wilson’s Existential Literary Criticism: A Guide for Students (Paupers’ Press, 2014) on this website.

Wilson realised that existential criticism constituted a revolt against prevailing values, or the lack of them, but that the existential critic possessed a standard bigger than himself, or any individual author, which was capable of revealing the ideal aim of all art.

Thus he goes further (in The Books in my Life) to assert that the purpose of all literature is ‘to become so absorbed in an imaginary world that we become suddenly aware that in the battle between the world and the mind, it is the mind that is destined to win’

And this brings me to the second salient point. You’ll not find existential criticism in any textbook of literary theory or manual of literary criticism, doubtless because it did not originate in academia, although this in no way diminishes its relevance.

Tsunami of theory

As I have written elsewhere (see link to review, above), it is ironic that Wilson, who was one of the first critics in the twentieth century, in the English-speaking world, candidly to spell out a literary theory, should have been eclipsed by the tsunami of theory from the 1960s which failed utterly to acknowledge his work.

The third point which impresses – although its implications for today are harder to quantify – arises from the concluding essay in Eagles & Earwigs, ‘Personal: Influences on my writing’, dated 1958, where Wilson, in the final sentence, remarks upon ‘the tradition of an intellectual creation’ in literature.

He writes that this tradition, begun by T S Eliot (whom Wilson regarded as a failed existential critic), was being continued by the Swiss novelist and dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921-1990) ‘with its roots in analysis, and its eventual aim to be a new form of self-consciousness’.

Wilson, in the early 1960s, saw Dürrenmatt as ‘the heir of the existentialist tradition’ stretching in literature from Goethe to Sartre, as he wrote in The Strength to Dream (1962), and how Dürrenmatt’s work was in ‘revolt against the makeshift standards of the modern world’. Dürrenmatt used ‘all the traditional analyses of existentialism, the concept of an inauthentic existence, human self-deception, etc‘, yet with an ‘instinctive, mystical optimism’ – he was a creator of positive values.

So if by ‘new form of self-consciousness’ Wilson meant awareness in literature of those attributes quoted in the preceding paragraph – a phlegmatic appraisal by writers of the capacity of the inner life to raise awareness of positive human potential – then one feels, regrettably, that he was being over-optimistic.

As Wilson says, any attempt to impose a scheme of values in literature at least would have the virtue of forcing its opponents (or indeed, writers and critics in an encounter with existential criticism for the first time) to scrutinise their own values.

Such salutary scrutiny, as a step towards the existential position, is as much needed today as it was more than half a century ago, if not more so.

NEWSFLASH!

In a publisher’s statement for Eagles & Earwigs, Todd Swift mentions how the world, for Wilson, flashed with G K Chesterton’s ‘absurd good news’, and adds ‘secular it may be, but good news nonetheless. Here in this book is some of it for you’. Indeed, but Dr Swift’s comment raises an interesting issue.

I believe Wilson first used the phrase ‘absurd good news’ in print in the booklet Poetry and Mysticism, published by City Lights Books in San Francisco in 1969. The booklet went on to form chapters 1-4 of the book Poetry and Mysticism (1970) in which the first chapter was actually titled ‘Absurd Good News’ – ‘the sudden feeling that everything is good, and that the human inability to see this is sheer stupidity, a kind of colour blindness’.

However – and I must thank Colin Stanley for this reminder – Nicolas Tredell, in his lecture for the first Colin Wilson conference, printed in the Proceedings, wrote: ‘Wilson often uses the phrase “absurd good news” and attributes it to G K Chesterton, although Chesterton’s actual phrase seems to have been “impossible good news”, in the penultimate paragraph of his novel The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908). In a journal entry dated February 8, 1956, Wilson speaks of “fantastic good news (Chesterton’s phrase)”. It appears Wilson slightly misquoted, or misremembered, twice!

This is the passage in The Man Who Was Thursday: ‘But Syme could only feel an unnatural buoyancy in his body and a crystal simplicity in his mind that seemed to be superior to everything that he said or did. He felt he was in possession of some impossible good news, which made every other thing a triviality, but an adorable triviality.’

Later, in The Occult (1979), Wilson equated ‘absurd good news’ with the mystical experience – ‘the joy that burst on Faust as he heard the Easter bells, the overwhelming feeling of insight that often accompanies the sexual orgasm’ – and, in Beyond the Occult (1988), he wrote that it was to express such ‘flashes of “immortality”’ that Chesterton coined the phrase.

Significantly, the phrase appears in the first few pages of Superconsciousness: The Quest for the Peak Experience (2009), where Wilson defines ‘absurd good news’ as ‘a sudden sense of wonderful optimism about the future, the feeling that life is infinitely complex and infinitely exciting’.

Therefore, to me, the experience of ‘absurd good news’, in the context of Wilson’s repeated use of the phrase in his works over a period of 40 years, relating it to the ‘peak experience’ and ‘superconsciousness’, is metaphysical, not secular, although it might have secular results. And what an appropriate misquote it is in this context!

What is meant by ‘metaphysical’ here? Broadly, that which deals with issues transcending physical matter or the laws of nature, with profound questions of being and knowing, of faith and belief – exactly the questions which the peak/mystical experience raises in the individual.

As Nicholas Hagger, with whom Wilson was acquainted, says, in A New Philosophy of Literature (2012), Wilson’s philosophical and cultural works signify a lifelong metaphysical quest for ‘Reality’, by which Hagger meant an infinite order behind and within everyday life. Hagger shows that this quest was originally stronger in world literature than secular writing.

GEOFF WARD

The Surrender of Silence: The Memoir of Ironfoot Jack, King of the Bohemians

Strange Attractor Press (UK £12.99, September 2018)

In 1957, Ironfoot Jack Neave, self-styled ‘King of the Bohemians’, left the manuscript of his picaresque memoir The Surrender of Silence with Colin Wilson, the two men having become acquainted some years previously, probably in Soho, when Wilson arrived in London in the early Fifties.

Jack hoped Wilson would be able to find a publisher for him, but Wilson was unsuccessful in this and, in 1959, Jack died.

It wasn’t until 2016, three years after Wilson’s own death, that the typed carbon-copy manuscript was discovered among Wilson's papers by his bibliographer Colin Stanley who grasped the significance of it and, to his credit, set about editing and annotating the text for publication.

And now, more than 60 years after its genesis, the book has finally appeared in print – rescued from oblivion – with introductions by cultural historian Phil Baker and Colin Stanley as editor.

Jack crops up twice in Wilson’s 1961 semi-autobiographical novel Adrift in Soho – ‘He was a strange looking man, a cross between a tramp and a character out of The Prisoner of Zenda’ – and Wilson had thought about dedicating the book to him, the only character in Adrift in Soho given his real name. Ironfoot Jack is also a character in the film version of Adrift in Soho (2018), directed by Pablo Behrens.

Variously, during his life, Jack Rudolph Neave (b1881 in Australia) – a well-known if infamous Soho character in pre- and post-war London in his standard attire of cloak, cravat and wide-brimmed hat – was an escape artist, fairground strongman, astrologer, numerologist, night-club promoter, founder of a quasi-religious sect, raconteur and, most of all, the deviser of numerous dubious ‘fiddles’ to make money and circumvent the system – in other words, a con-man, albeit a benevolent one.

His nickname arose from an accident which shortened his right leg and required a metal device on his boot, hence ‘Iron Foot’. He gave various tall stories about the accident, including a shark bite while pearl-diving, an avalanche in Tibet, and being shot while smuggling.

Jack’s account of his career on the streets traversing the British demi-monde in the first half of the 20th century is genuinely fascinating in its evocation of lifestyles long vanished. However, as he dictated it while having his portrait painted in 1956, and then had it typed up, what we have is not considered prose from a practised writer but one long, rambling direct quote in Jack’s self-congratulatory tone.

Its title remains a puzzle and open to interpretation, as Jack does not explain it (he didn’t have to, of course), but perhaps we can see a ‘surrender of silence’ in the Bohemian hubbub in which Jack was enveloped, or maybe just in his malapropist monologues - or, as Colin Stanley himself has suggested, Jack’s telling of his story at last at age 76, with only two years left to live as it happened,, was itself ‘a long silence surrendered’.

With a smattering of knowledge about occultist and esoteric subjects, Jack liked to pass himself off as a kind of mystic or would-be guru, a 'professor' of the arcane. Indeed, ‘his ignorance never failed him on any subject’, wrote Mark Benney in his 1939 biography of Jack (What rough beast? A biographical fantasia on the life of Professor J R Neave, otherwise known as Ironfoot Jack. London: Peter Davies).

Yet while Jack’s memoir is an interesting social document, it is hardly what Jack himself said of it: ‘the greatest book ever written on Bohemians in Europe’, as he told Colin Wilson in a letter in 1957. Had Jack lived longer he doubtless would have seen himself as a precursor, or even founder, of the Sixties counter-culture.

The Surrender of Silence was the outcome of years of struggle to survive, Jack wrote, of day to day efforts to ‘solve the problem of existence’ – one of his favourite phrases, indicating not a philosophical exercise but simply a pragmatic one of making enough money, ‘by various and curious methods’, to survive on the streets.

Most of the people he knew – gipsies, travellers, show people, buskers, fairground workers, market traders and poverty-stricken artists and down and outs – led precarious lives, winning their livelihoods from day to day. ‘They worked to live, they did not live to work,’ was Jack’s oft-repeated mantra, his summation of the Bohemian world-view.

In the memoir, Jack is exceedingly coy about the Caravan Club scandal of 1934 which led to a 20-month prison sentence for him, as well as about a later jail term he served in Birmingham. The Caravan Club was gay and lesbian-friendly and tolerated low-level criminality and prostitution. Jack and many others were arrested in a police raid; he was charged with running a disorderly house. The trial at the Old Bailey was described in Benney’s biography which, said Jack, perhaps ruefully, made for ‘a good education for the sociologists’.

In that 1957 letter to Colin Wilson, Jack added: ‘I have written The Surrender of Silence not so much for my material gain but to the memory of a glorious past of Bohemian life which is now gone with the wind leaving behind only memories and a brief spell of passion and strife.’

A number of appendices to the memoir, providing a good measure of ‘bonus material’, comprise a series of congenial letters written by Jack to Colin Wilson, an article about Jack entitled ‘Ironfoot – last of the Bohemians’ from Reynolds News in 1958, a pamphlet, The Drama of Life, written by Jack, and Jack’s numerological ‘4 Advices’.

A literary curio, one must say, but revealing in its descriptions of streetlife, particularly of the 'underground' London of Jack's day and its fly-by-night denizens and their seedy dives, now almost lost to living memory.

* Ironfoot Jack appears in a Look at Life: Coffee Bar film (in the French coffee shop at 5.29) shot in Soho in the 1950s. GW